“Crisis” is an overused word. Actual crises are those rare times when we are on the knife edge of disaster. It’s not a crisis when a bank fails, or Congress can’t agree on a budget. Those are annoyances (unless it’s your bank). While not good, they don’t spell immediate catastrophe.

I’ve long been predicting a global debt crisis that will lead to a giant, worldwide restructuring. I call this the Great Reset (a term the Davos people later appropriated). One of my top takeaways from the Strategic Investment Conference was that this crisis isn’t just inevitable; it is necessary. It’s what will allow us to do the unthinkable.

Excessive debt isn’t quite an extinction event but it’s still a giant problem. After SIC, I’m more confident we’ll find a solution. It will happen the same way we solve other problems: when we have no other choice.

Budget Futility

Federal debt was in the headlines recently as the government approached its statutory debt ceiling. The experts I trust mostly thought we would avoid default, but the process would be ugly and politicized. That’s more or less what happened. After much angst, Biden and McCarthy agreed to extend the debt ceiling to 2025, freeze discretionary spending, and make a few other small changes.

To me, the most interesting thing they did was to require a 1% decrease in spending if Congress fails to approve budgets for the next two years. Technically this is called a sequester. Given that they rarely pass a full budget but just keep making continuing resolutions, it will be interesting to see if that 1% cut produces majorities in both House and Senate. I’m sure no one will be fully satisfied, but this forced cooperation might be worthwhile.

As for the other changes, a big Republican demand was enhanced work requirements for food stamps (SNAP). Currently the work requirement only applies up to the age of 50 and only for those with no dependents. Under this deal, that goes up to age 54. But the deal also adds new exemptions for veterans and homeless people which may actually increase SNAP spending. It certainly won’t starve millions, as some Democrats complain. After all this drama, only a few additional people will have to work for their SNAP benefits and the budgetary effect will be nil.

That illustrates the futility of budget negotiations. Any change significant enough to matter draws vigorous opposition from those who depend on the status quo. Every spending program has a well-organized constituency. Politicians of both parties pay attention, so we get a lot of noise and little real action. It’s more structural than political. Avoiding default was great but this deal was yet another missed opportunity to rein in debt growth, which will continue and even accelerate.

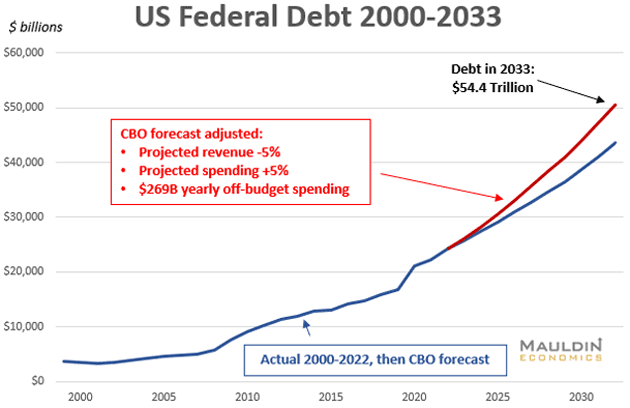

Here’s a chart I shared a few months ago in Deficits Forever. Using CBO data and some realistic (or even conservative) assumptions, we estimated federal debt will easily surpass $50 trillion in the early 2030s. The latest deal does nothing to help. And if interest rates don’t come back down that total debt number will be higher. It won’t be long before we will be paying $1 trillion just in interest every year. Ugh.

This is just the government debt. According to U.S. Debt Clock, Americans have another $25 trillion in personal debt (mortgages, car loans, credit cards, etc). Not to mention untold trillions in debt issued by large and small businesses. We are living on borrowed money.

You can do the same exercise for almost every developed country and for many developing countries. The Great Reset will be a global phenomenon.

Relative Debt

On SIC Day 5 I had a fascinating conversation with William White, former chief economist at the Bank for International Settlements and veteran central banker. Bill speaks far more openly than most of his peers, and also isn’t reluctant to criticize. That makes him my favorite central banker. We talked about the debt situation and how it will play out.

Bill and I basically agree that there will be a reckoning in the not-too-distant future, likely sometime the latter part of this decade. I asked Bill whether we will rationalize the debt through inflation or deflation. For years, Bill has been telling me that both deflation and hyperinflation are possible. I questioned him a little bit more aggressively than usual, asking him to define the conditions that would bring about either outcome.

His answer was both surprising and clarifying. He thinks it will depend on whether the problem is primarily government debt or private sector debt. Here’s Bill from the SIC transcript:

“The private sector is deeply indebted. In the US, the households have come back a bit, which is good, but looking at it sort of globally, private sector debt has risen enormously. When you look at government debt, it’s almost exactly the same thing. It’s risen enormously. And in a way, this is how I think of it anyway, if we have real problems on the private sector debt side, that’s going to drive us more into the deflationary outcome. If we have problems more on the government debt sustainability side and it’s the government that’s got control of the printing presses, then you’re going to have more likelihood of an inflationary outcome.”

That made a lot of sense to me. Central banks are responsible to governments, and thus more likely to create liquidity when their government is over its head in debt. That’s an inflationary scenario. Conversely, if it’s the private sector which is most overindebted, central banks are more likely to let that debt deflate. That’s what happened in 2008.

Yet the lesson central banks have learned in such a situation is to provide liquidity to markets, and they will keep doing that with each crisis until it no longer works. That leads to a sovereign debt crisis and higher inflation.

At that point, central banks will be powerless and the government will be forced to get its own house in order. That will be the necessary crisis I mentioned above.

Keep in mind, we’re talking relative debt here. Governments, households, and businesses are all in trouble. In the end, Bill thinks we may see both very high inflation and deflation as well. None of the scenarios are good. They’re simply different.

Bill said once we get past the initial stages, people will start questioning the institutional structures that let it all happen. That crisis of confidence in institutions and government, coupled with the economic chaos that it creates, will make the public want to “fix things.” That led nicely to our final panel where Bill reappeared alongside Neil Howe and Felix Zulauf.

’This Is a Country Capable of Miracles’

I design the SIC final panel to pull the pieces together. This one did exactly that with an unexpected twist.

Like I said above, the panelists didn’t just foresee a crisis. They welcomed a crisis because they see it as the only way out of this mess. Let’s start with Felix Zulauf:

“I’m a very optimistic person and a very happy one. As an analyst and coming from the macro side, I have a bias to skepticism, of course. And my expectation for the next 10 years is one of major change in geopolitics, in economics, in the way the world is run. I think Neil has laid the groundwork for that with his Fourth Turning. I used to think that we repeat the mistakes of our grandfathers, but it’s probably even our great-grandfathers.

“What I think is we cannot continue to run the world the way we have run it for the last 30 years. And human beings are lazy by nature, and they try to continue in a way it has worked in the past. And they will only change if they get forced to change. So, I think we will run into several brick walls that will stop the trends of the past and force us to change. And this has to do with fiscal policy, with monetary policy, with geopolitics, demographics changing, etc. I think we are in for some rough times, and I could even see some depression in the later part of the ’20s, a depression that will be very different from the depression of the 1930s.

[Later Felix clarified that he thinks it will be a depression of down 3% a year for three years rather than the down 25% of the Great Depression.]

“In the 1930s, we had a fixed exchange rate system based on gold. It was fixed and rigid. This time we have a fiat currency system. I think last time, they let the economy go down, and the currency remains stable. I think next time, they will try to save the economy and let the currency go down. And this leads to what Bill alluded to in his previous session, that there is a risk that we could have some major write-offs in debt, and write-offs in debt means eventually risk of currency reforms and things like that. I think we are going through a very difficult, structural, and secular change to a transition period into a better 2030s.”

Now let’s turn to Neil Howe:

“What we face over the next decade is a very sobering environment. We have two leaderless parties in the United States, driven by debilitating partisanship, leading a government that’s currently heading into default in a world surrounded by building great power threats… Moreover, we have all of the long-term recession indicators pointing to a downturn at the outset of a decade, which we know, in demographic terms, is going to be record-low economic growth, not only for the United States but for the developed world and even the emerging economies, just driven by demographic reality, very little working-age population growth. This is a very challenging environment which could go critical at any time.

“I think the upside of the decade we’re moving into is that great challenges, particularly when they become crises, galvanize people to engage. And that’s what gives me optimism because Americans always have a wonderful track record once they are fully engaged citizens. This is a country capable of miracles, but it is going to require that kind of urgency, that kind of engagement.

It’s not going to happen on a sunny day, and that’s [the crisis] when we make our great decisions. I do expect a lot of trouble, both domestically in politics with the economy, with financial markets, and particularly compounded by kind of the great power kind of risk situation.”

You think we need a miracle? We’re capable of them when we are sufficiently motivated. And we will be. Neil picked up this theme a little later:

“John nailed it on the head when he said that the fundamental contradiction in our current policy regime is not monetary policy, it’s fiscal. There was no question about that.

“In order to actually balance our budget or just make it sustain—forget balance, we’re never going to balance it—but just make it sustainable on a long-term basis, we’re going to have to have huge reductions in both entitlement programs… where all the long-term growth is, by the way. It’s all in entitlements. We can’t cut defense really at this point, and we are going to have large increases in revenues. And probably on top of that, we’ll need at least some large one-term inflation hit to basically do what we did after World War II… getting rid of a lot of our debt simply by inflating our way out of a lot of it before people readjust their expectations.

“We’re going to have to do all three of those. And what I’m saying is politically, we are nowhere near that ever happening. Our country would right now break in two pieces rather than come to an agreement like that. We’re going to have to be scared into it. And I think this is why crises become actually useful, right? Because they motivate people.”

I have to say, this was the strangest mix of doomsaying and optimism I can remember in 19 SIC events. David Bahnsen asked Neil if he thought the American people were still capable of doing what it will take. Neil had no hesitation.

“I remain very optimistic, and I think leadership and policies do absolutely reflect the people. They reflect the social mood. And as I point out in my forthcoming book, I have a lot of confidence that today’s generations can respond very favorably to crises. It will take a crisis, but I have no doubt that they can respond favorably.”

Neil has been saying since the 1990s the Fourth Turning would shake the country to its core and one particular generation would lead us out of the abyss. Last time around it was what we now call “The Greatest Generation” who pulled the country through the Great Depression and fought World War II. Their successors are the Millennial generation, children of the 1980s and 1990s. They will gain influence as my generation begins leaving the scene. Neil Howe thinks they will do what it takes.

We only touched briefly on the fact that both Neil Howe and George Friedman and others are predicting a serious conflict accompanying this economic crisis. The problem is we don’t know where the conflict will come from or what it will be. Will it be an internal conflict within the US and other countries? Will it be a geopolitical conflict? We have no way of knowing today.

The crisis—and that’s exactly the right word in this case—will be agonizing and painful for many. But it has to happen. And we will get through it. Together.