World Economy and Trade: Where We Stand As We Close the Year

Since the February correction, the U.S. stock market in 2018 has struggled under two major psychological clouds: the risks posed by global trade conflicts, especially the trade relationship between the U.S. and China; and the end of the post-crisis era of ultra-low interest rates.

Escalating trade conflicts caused analysts to doubt the forward path of earnings growth for the majority of large U.S. companies, which generate much of their profit overseas, as well as those who rely on materials and finished goods imported from abroad that might fall afoul of new tariffs. For some, these trade worries derailed the thesis of a “coordinated global growth uptick” that had prevailed during more optimistic times in 2017, and brought forward the prospect of an economic slowdown that could lead to a recession. Perhaps the U.S. would go into recession, or perhaps it would be confined to countries outside the U.S. — but in any event, growth assumptions would be challenged. Recession fears emerged, and the market accordingly became more volatile and fell in price.

Trade fears surfaced first in 2018, but interest-rate fears arose in the second half of the year, as market participants nervously interpreted Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell’s plans for future interest-rate hikes. Market participants, we believe, misread Mr Powell’s intentions, and began to fear that the Fed would raise rates heedlessly and mechanically, independent of developments in the U.S. and global economy. That led to a fear that the Fed’s tightening would invert the yield curve — that is, cause short-term interest rates to rise above long-term interest rates and choke off the credit cycle, eventually tipping the U.S. into recession. So once again, market participants had found another reason to fear the “R” word — and perhaps begin to price in a recession starting in 2019.

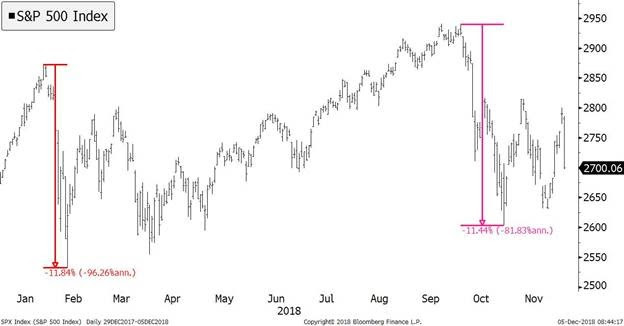

The S&P 500 has experienced two significant corrections greater than 11% in 2018.

The S&P 500’s Rocky Road in 2018…

The declines in the S&P 500 masked even more significant declines in the expensive, high-growth stocks that had provided much of the market’s momentum and returns since 2016. The performance of the tech- and innovation-heavy NASDAQ index reflected these more significant declines.

… and the NASDAQ’s Even Rockier Road

Source: Bloomberg, LP

With all of that said, where do we believe things stand as 2018 comes to a close?

Regarding the two dominant fears of 2018, we continue to believe that fears are exaggerated. But we also note that market psychology changed several weeks ago from bullish and optimistic, to bearish and pessimistic. Long-term we see great things ahead for an increase in U.S. economic growth and living standards. But we also realize that markets operate on a cyclical basis. Currently, the markets have entered a more pessimistic phase, with a “show me” attitude — and stocks must prove that they deserve to be owned and sell at substantial valuations. This is a difficult environment for most companies, and only those who can truly grow and surpass expectations will do well. Accordingly, we are holding large cash balances for clients, earning interest while we wait for opportunities to buy quality stocks at reasonable valuations.

Currently, the U.S. economy is not going into recession. But pessimism must shift before stocks begin to attract new capital and move ahead. The U.S. economy is still growing. The message from pundits that Fed Chair Jerome Powell was hell-bent on a predetermined course of interest rate hikes, come what may, was just a fear-based reaction. We believed that Mr Powell was simply being plain-spoken and straightforward about his views, and that he did not elaborate sufficiently on the data-dependent nature of Federal Reserve policy to calm the anxious. The Federal Reserve is a vast institution, with hundreds of trained economists in the ranks of its bureaucrats. As an institution it can certainly make mistakes (as history has shown on some occasions), but it would be unreasonable to suggest that the Fed would simply ignore economic developments and charge ahead on a predetermined course. Our view was vindicated when Chairman Powell made remarks last Wednesday that affirmed the Fed’s data dependence, and markets were briefly mollified.

Second, trade. Here the news is mixed. Recently, the leaders of the world’s leading 20 economies gathered in Argentina. This G20 meeting created a lot of optimism about the path to the resolution of trade issues, particularly between the U.S. and China. China pledged to remove the 40% tariffs imposed on U.S.-made automobile imports into China. The agreement between Presidents Trump and Xi has several major components to be implemented, and there is an initial 90-day window to make progress on solidifying the proposed deal.

Two parts of the agreement could be easily consummated within the next three months, and three parts are longer-term issues that could prove more difficult. U.S. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin has said the U.S. negotiators have reserved the right to extend the three-month period if progress was being made.

Here are the easier fixes. China agreed to buy more from the U.S. This will include shifting the purchase of natural gas and farm products to the U.S. from other countries such as Australia and Qatar; shifting soybean purchases from Brazil to the U.S.; and buying more machinery from U.S. manufacturers.

Perhaps financial services providers will be able to offer credit cards in China without a local partner who gains access to their network and part of their profits.

Also fairly easily solved is an agreement to lower tariffs from both sides. The average Chinese tariff today is 9.8% on foreign goods entering China, and the average U.S. tariff (after the recent increases) is 3.8% on foreign goods entering the U.S. Both countries will move tariffs toward zero. Further, we expect China to announce to the world that their tariffs are coming down — perhaps in January when global political and business leaders gather at the annual conclave in Davos, Switzerland. China may take the opportunity to make themselves look like a leader on lowering tariffs.

We expect progress on these two areas in the next 90 days.

The remaining three issues are much more difficult to solve, and will only be solved over the longer term.

First, forced transfers of intellectual property to Chinese partners from all foreign companies who do business there. Under these rules, Chinese joint venture partners have gotten U.S. technology even though it was their U.S. partner who created it and patented it. The Chinese companies get technology just for putting up the legal framework and some money, or perhaps becoming an important marketing conduit. Many believe that this is a matter of geostrategic importance; it is a big concern of the U.S. administration, and, we believe, a key component of China’s long-term global economic and political strategy. Reaching a deal, and more importantly, ensuring that it is observed, will be tough.

Second, China’s provision of major support for favored domestic industries. The subsidization of these favored industries has included unfair trade practices as well as state financial and technical support and penalization of foreign competitors. This kind of policy is also employed by Japan and Germany, and to a small extent by the U.S. itself.

And finally, Chinese industrial and strategic cybercrime — breaches of U.S. data, and spying on U.S. companies. This again will be a thorny issue to address, and a thornier issue to implement and enforce.

We are hopeful that progress will be made in the next three months, as it is in the strong interest of both Chinese and U.S. leaders to make that progress. The two “easy” areas we mentioned will likely be dealt with. We believe that on the basis of the U.S. president’s long history of opinion on this issue, that it is important to him to make progress on solving the three more difficult issues that we described above. We think that the deal will allow for that progress to be gradual — and that means that there will be plenty of opportunity for the market to regain some optimism.

Still, the damage to market psychology from the year’s volatility, and multiple corrections, has been serious. As is our style, we are currently holding large cash balances for most of our clients as we look for bargains created by the declines, and wait for a shift in psychology that signals some of the damage has been healed. We still do not believe that a recession is likely to begin in 2019, and we think that the market’s pricing in of a recession is premature. During Tuesday’s decline, we noted that recession fear was rekindled by the inversion of one yield curve, when five-year rates fell below three-year rates. The violence of the reaction shows that market participants are still in a “sell the rallies” mode. Until that shifts, even though we remain fundamentally optimistic about the underlying economic trends in the U.S., we will wait and watch for the appropriate time to invest more aggressively.