Central banks’ purchases create a floor for gold prices. Myth or fact?

We invite you to read our today’s article about the central banks’

demand for gold and find out whether it will save gold.

Gold is an important part of central banks’ foreign exchange

reserves. As of H1 2018, they hold about 34,000 tons of bullion worth

$1.36 trillion, or 10.3 percent of the total reserves, according to the World Gold Council.

Interestingly,

we have recently seen the increased interest in gold. In the first nine

months of 2018, central banks purchased more than 350 tons, the fastest

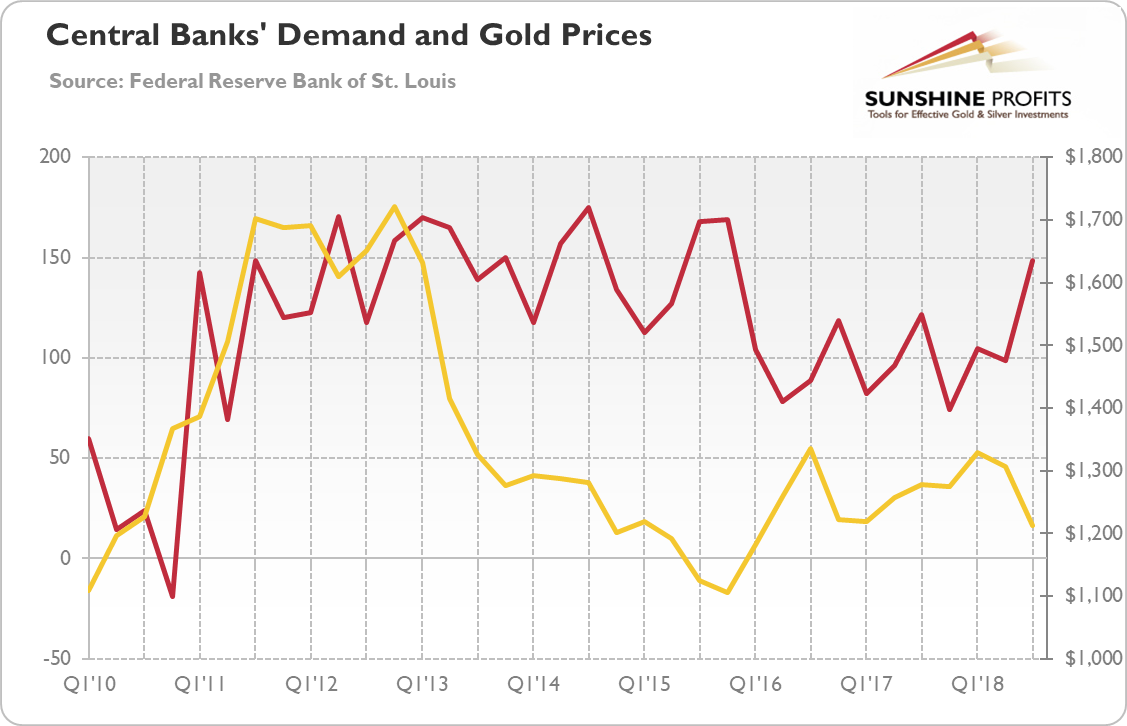

pace of accumulation since 2015. In sole Q3 2018, central banks bought

more than 148 tons, 22 percent higher year-over-year. It was the highest

level of quarterly demand since Q4 2015, as one can see in the chart

below.

Chart 4: Central banks’ demand (red line, left axis,

in tons) and the price of gold (yellow line, right axis, London P.M.

Fix, in $) from Q1 2010 to Q3 2018.

What

is important is that more central banks joined the list of gold

purchasers, which means that the gold’s appeal is widening. While

Russia, Turkey and Kazakhstan continued their buying, other players

decided to buy the yellow metal as well. For example, Egypt bought gold

for the first time since 1978, while India added gold to its assets for

the first time in almost nine years. Also Indonesia, Thailand and the

Philippines re-entered the market after multi-year absences.

Moreover,

the National Bank of Poland made its first purchases of gold in 20

years, while the Hungarian National Bank added more gold to their

reserves for the first time since 1986. Their purchases marked the first

growth in gold reserves within the European Union so far in the 21st century.

Hence, the questions arises. Why are they buying? Does that mean that the price of gold is going to rise? Do the central banks’ purchases of bullion provide a floor for its price?

Although

it’s tempting to assume that central bank are buying gold because they

possess some inside knowledge about the upcoming financial crisis for

which they want to be prepared, there is a much more prosaic reason. The

gold price has declined more than 6 percent so far this year (since

January 2nd to November 7th). After such a drop, gold might look as an attractive alternative to other foreign currencies, US dollar in particular.

It suggests that the central bank demand does not drive the gold prices. One thing is that it is simply too tiny in comparison to the overall gold market. It makes about 13 percent of the annual new gold supply calculated by the WGC, which itself constitutes a small percentage of the total gold holdings. But another is that, as we have seen, central banks tend to buy gold when its price declines. So the gold prices drive the central bank purchase, if at all, not the vice versa.

Or,

actually, the link between the central banks and the bullion prices may

be even weaker. Joshua Aizenman and Kenta Inoue analyzed the patterns

of gold holding and trading by central banks during 1979-2010 in their

paper “Central Banks and Gold Puzzles”.

They found that generally central banks maintained passive stocks of

gold, independently of the patterns of the gold prices. Just look once

more at the chart above: as you can see, the quarterly demand remained

within a narrow range during 2013-2015, although the price of gold

plunged.

This is because the intensity of holding gold has more to do with signaling economic might.

Indeed, among buyers there are countries with a strong need to signal

their power, especially relative to the ‘rotten West’, like Russia or

Turkey. And it might not be a coincidence that Poland and Hungary, which

are supposedly turning away from constitutional democracies, joined

the club of gold buyers.

Summing up, the central banks continue

buying the shiny metal. Actually, they increased their demand for

bullion, which indicates that the gold’s appeal as a safe haven or a portfolio diversifier is widening.

However, despite some mistaken opinions, it is not a bullish sign.

If the central bank purchases have something to do with the level of

gold prices (which is not certain), it is a testimony of previous

declines. Investors should drop their hope that the central bank demand

will provide a floor for the price of gold. The history shows that official purchases did not prevent the deep dives in prices.

Moreover, do you remember the Brown Bottom?

The UK sold half of its gold reserves, and the price declined just

8.5%. But very soon gold started its tremendous bull market (see the

chart below), which puts the ability of official transactions to affect

the gold prices in a sustainable manner into question.

Chart 5: Gold prices in British pound from May 1990 to November 2018.

And

it was at the turn of 1990s and 2000s, when the price of gold was much

lower, while the gold market less liquid. Now, given a few times higher

prices and highly liquid market, the amount of gold needed to affect the quotation is prohibitive – and its impact would be only short-lived.

If you enjoyed the above analysis and would you like to know more

about the macroeconomic outlook and the gold market, we invite you to

read the December Market Overview

report. If you’re interested in the detailed price analysis and price

projections with targets, we invite you to sign up for our Gold & Silver trading Alerts.

If you’re not ready to subscribe yet and are not on our gold mailing

list yet, we urge you to sign up. It’s free and if you don’t like it,

you can easily unsubscribe. Sign up today!

Thank you.

Arkadiusz Sieron, Ph.D.

Sunshine Profits‘ Gold News Monitor and Market Overview Editor

Gold News Monitor

Gold trading Alerts

Gold Market Overview